Joan Ruiz i Solanes (1945-2024)

Prehistorian, archaeologist

former member of Société Préhistorique Française

June/July 2023 ©

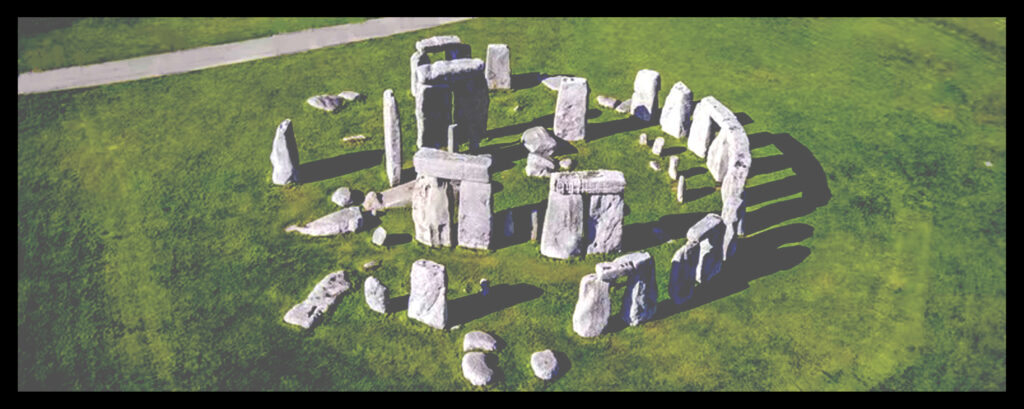

The asymmetry of the temporal dimension prevents us from going back into the past to verify the truth or mistake of our historical statements. We must resign ourselves to reinterpreting the facts accomplished in real past time based solely on the vestiges and signs that the passage of time has preserved. Two of the greatest vestiges we have inherited from recent prehistory are the Stonehenge circle and the great alignments of the Carnac menhirs. The grandeur of these two monuments is an indication that it has not always been well interpreted. Stonehenge has often been considered a temple, a funerary monument or an astronomical observatory. The alignments of Carnac have been considered great avenues of disappeared temples or palaces, great necropolises or, also, astronomical observatories.

Neither the studies on the ground nor the reflections in the office have made it possible to obtain a definitive criterion. Although we have managed to detect the solstice orientations of these monuments, this is not sufficient reason to consider them astronomical observatories and, unfortunately, it does not seem very realistic to assume that Neolithic peoples had such a great fondness for knowledge that motivated them to devote such considerable efforts to astronomy, especially when with a simple stick or rock planted on the ground the summer and winter solstices can be easily determined.

FIRST QUESTIONS

When at the end of the last century, in the mid-80s, I became seriously interested in the Stonehenge monument, I was soon intrigued by a particularity that at the time I could not explain. It was about the transgression of an elementary, indisputable and very ancient rule of polyorcetics, that is, of the technique of building and attacking fortifications, a rule that tells us that whenever there is a moat and an embankment, palisade or wall, the moat must be located on the side of the person trying to enter and is not well received, that is, outside. This is how the depth of the moat is added to the height of the embankment or wall, making the fortress even more impregnable.

Well, at Stonehenge the opposite happens: the embankment is outside and the moat is inside. This rare distribution of the building elements intrigued me; for some weeks I tried to find a logical explanation of the phenomenon but success did not smile on me.

FIRST ANSWERS

The years passed and, in the first decade of the 21st century, I had the good fortune (without underestimating the constancy of the work) to begin to understand some of the oldest inscriptions of the Catalan Countries, the Iberian epigraphs. Although it may seem strange, the concepts learned in this activity allowed me to understand why the incomprehensible (?) strangeness of Stonehenge.

In fact, if I had thought calmly I could have quicklyunderstood why the moat was inside the embankment. A very simple reason, the only one that explains the irregular arrangement of that monument elements: that kind of construction was not done to prevent the entry of any enemy, but to prevent the exit of someone who was already inside the enclosure.

Of course, it remained to find out who could be the person or people locked in that kind of monumental prison.

Person/people? A kind of construction that required so much efforts, so much planning and so much labor for its erection would have been intended for some mere prisoners? No, it couldn’t be. So who was to prevented from leaving the enclosure?

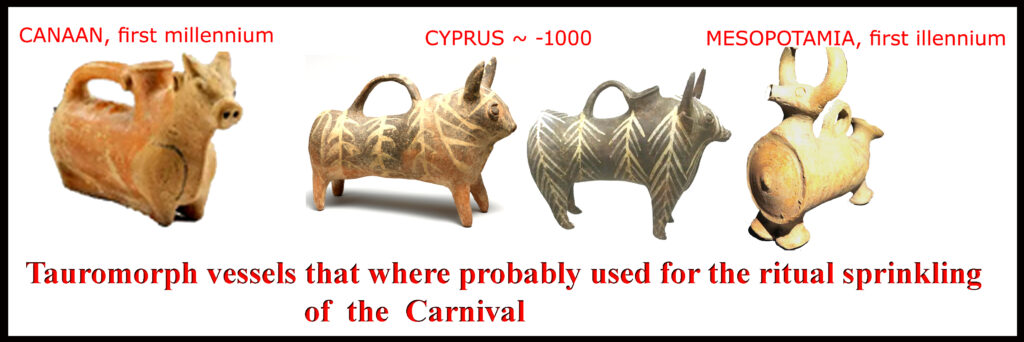

… Then the Iberian epigraphy clarified the apparent mystery for me: it was not a person but an animal. The essential sacrificial animal of the greatest ancient festival of antiquity (the equivalent of our Carnival), the bull, which had starred in many cultural and artistic manifestations in the Mediterranean world: in Çatal Höyük, the Cretan taurocatapsia (Bull-leaping), the bucrania (bull heads) of the metopes of some Doric temples, the three bronze bucrania of Costitx in Mallorca, without forgetting the three sacred Egyptian bulls, Apis, Mnevis and Buchis…

THE GREAT ORGIASTIC DEBAUCHERY, THE ANCIENT CARNIVAL

The Ancient Carnival, a festival typical of agricultural towns, was the main incentive for the first Neolithic farmers to resist the harshness of a cumbersome existence. It was the greatest incentive to continue enduring those very hard agricultural jobs done with primitive tools, without the help of metals, still unknown. This festival was the necessary motivation for humans facing with lands that have never been cultivated, compacted and hard that opposed the resistance to the patient work of hoes of polished stone.

Without compensation like the debauchery of the old Carnival, life would not have been worth living. And it seems that there was no lack of orgiastic debauchery at that party, it seems that everything was allowed without any kind of moral restriction.

Carnival was also the celebration of the eternal return of the plant cycle analogous to the eternal generational cycle. Just as year after year, after the winter “death” of the vegetation, with the spring the grass grows again and the deciduous trees take their leaves, likewise the death of a generation give way to a new one that continues the cycle of birth-growth-death.

As has always happened in primitive societies, phenomena that are difficult to understand have generated myths. The case of winter death and vernal resurrection of vegetation was also explained through a myth: the so-called cycle of Bel.

BEL, THE BLACK CALF, AND MOT, THE OLD BULL

Let’s go back to the 30s of the last century, when the Alsatian Claude Schaeffer led a French expedition to Syria, to the tell or mound of Ras Shamra, where he excavated the remains of the ancient city of Ugarit.

There he found clay tablets written in cuneiform signs which, unlike the signs used until then, contained neither ideograms nor syllabograms, but only letters. They were alphabetic signs.

Good illustrations of the tablets were given to three orientalists, H.Bauer, E.Dhorme and C.Virolleaud, separately and without contact between them. When they concluded their respective studies and presented the results, it was found that all three versions were satisfactorily equivalent. The ancient Ugaritic language was deciphered.

Many of the tablets were of a commercial theme or palace inventories and receipts, but others dealt with what we know today as the Cycle of Bel or Ba’al.

Bel was a black calf, god of storms, rain and plant fertility. It also seems to be identified with the new year, which begun with the winter solstice. Mot was an old bull, also black, god of disorder, drought and misfortune, and was probably identified with the old year.

At a certain time of the year, both gods faced each other and fought to obtain the power immediately after the Sumerian supreme god An (corresponding to the Akkadian El) and coinciding with the last days before the winter solstice. During the waning and shortest days of the year, Mot defeated and killed Bel. If Bel had remained dead for good, an eternal winter would have reigned over the lands, the grass would have died, and with it the herbivores. Bel had to be resurrected imperatively!

Although it may surprise many people, the concept of resurrection is long before Christianity. One of the oldest gods of Pharaonic Egypt, even predynastic, and of an eminently agricultural nature, Osiris, had been resurrected. Seth, the brother of Osiris, had killed him, cut him into pieces and scattered the pieces on the earth, but Isis, Osiris´sister and wife, had gathered the pieces and sewn them together, bringing the god back to life.

Some authors believe that the cycle of Bel, due to the fact that it was handed down to us by the Ugaritics, must belong to the Akkadian religious ideology, that is to say Semitic, but it seems that the names Adad, Hadad, Addu or Ishkur were currently used in Mesopotamia.

But fairly solid indications suggest that just as the Akkadian Semites had adopted from the Sumerians the epic of Bilgamesh (as it was called in Emegir, the dominant Sumerian language) while turning him into Gilgamesh, they could also have adopted the mythology of Bel . The very name of Bilgameix seems to indicate this, the e and the i being two such close vowels.

Probably the evolution of the theonym through the centuries was Bil->Bel->Ba’al. And when it comes to the black calf, god of rain and grass, it is at least very curious that both the Basque language and the Iberian epigraphy present very suggestive coincidences: the current Basques still call beltz the color black, and belar the grass. I don’t have a clear opinion if both words are related to the theonym, but I consider the coincidence very significant.

We know this myth of Bel especially through the Ugarit tablets, Semitic, but these are terminus ante quem and not post quem. We know for sure that after the Akkadian version the myth was known, but we do not know if it was already known long before.

Of the tangle of gods that existed in Mesopotamia in the last millennia before the vulgar era, we only know a part and ignore many aspects such as the provenance and origin of each god.

Despite the fact that changes have been accelerating in recent centuries, faster the more recent, religions are more persistent, usually lasting longer than the same states where they were born (Christianity or Islam are two indisputable examples). Therefore, to think that the figure of the god Bel – with the same or different name – came from long before it was reflected in texts, is not nonsense. Naturally, we cannot prove that the Natufians, who did not know the writing, already knew this deity, but it seems very likely that this was the case.

Some scholars believe that the only way the knowledge of Bel could have reached our lands is through the Punic Baal or Moloch-Baal, already during the orientalizing period from the end of the 8th century or especially when the Barca family dominated the southern peninsula. But this entails denying, without any proof and against the evidence that Bilgamesh supposes, that the knowledge of Bel-Baal could have reached us much earlier, already with the first settlers of the Ancient Neolithic (NA).

Some indications make me think that a people like the one we call Natufian (-12,000 to -10,000 approx.) in the middle of the Mesolithic, already knew the Bel cycle. The descendants of that town, when expanding along the Mediterranean shores, spread the myth at the same time as the practice of the Neolithic agricultural economy.

LET’S DEEP INTO THE SUBJECT. THE FACTS THAT HAPPENED

Around the year -12,000 the climate conditions of the planet had been changing, the glaciers that had covered part of the Northern Hemisphere had been melting and receding, and this circumstance makes us consider that then the Holocene began, that is to say the current era.

On the eastern shore of the Mediterranean, from the north of the Sinai Peninsula to the southeast of Anatolia, the new climatic conditions favored people to base much of their diet on the harvest of grasses that would later become barley , oats or wheat cultivated and which the studies of Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov showed were originally from those regions.

The inhabitants of those places mowed the grasses with primitive scythes made of branches with embedded flint teeth, and ground the grain with hard stone mills, at first barquiform mills that centuries later would be replaced by rotary mills.

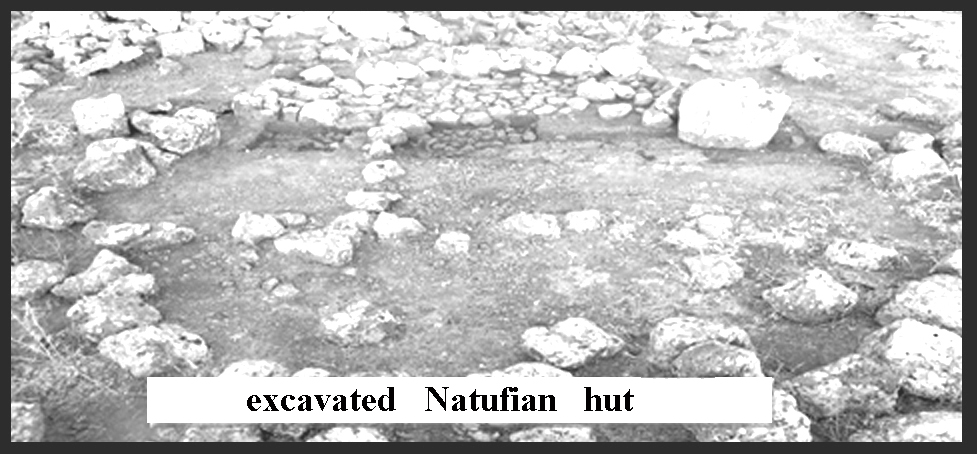

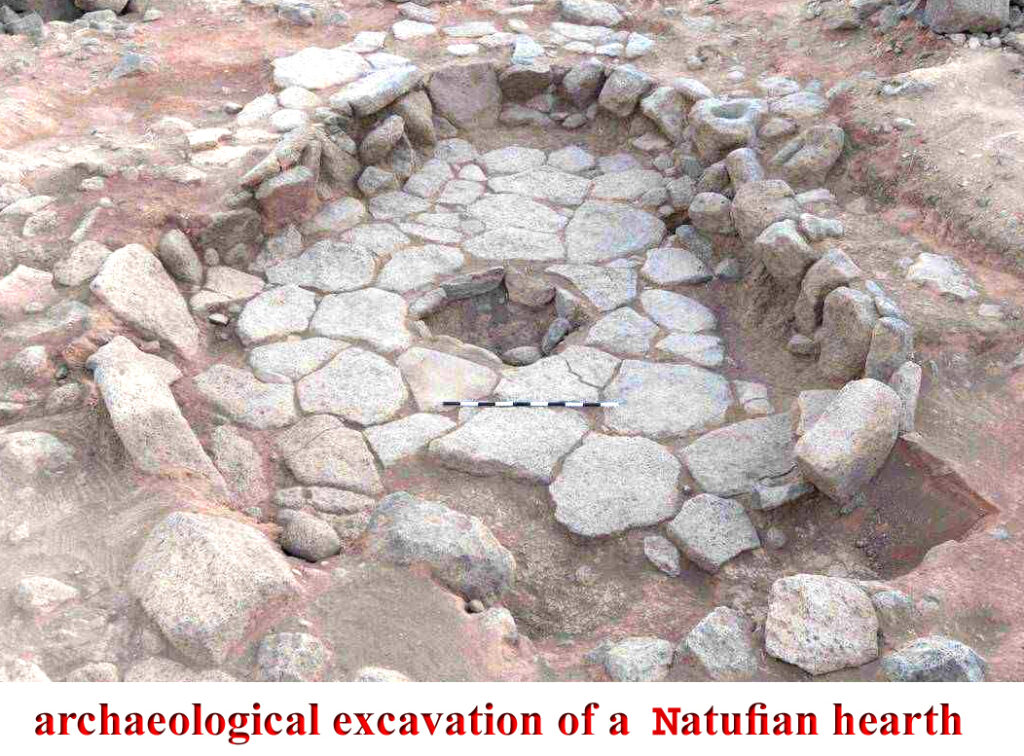

In 1932, the British archaeologist Dorothy Garrod exhumed the first vestiges of that civilisation, which she named Natufian because she discovered them in a cave in the Wadi-an-Natuf valley, in the west of Judea, West Bank.

Shortly after, the work of René Neuville and Jean Perrot continued to improve our knowledge of the Natufians. They discovered that in their early phases, the Natufians used to live in circular huts -isolated or in very small groups- which correspond to farms. I will call this “dispersed habitat”.

We currently know that they did not know agriculture. In addition to hunting, especially gazelles, they harvested almonds, pistachios, lentils and knew how to collect wheat, barley and oat grain, but they had not learned how to sow it.

Every year, when they reaped with their primitive sickles, the vibration of the harvest made the grains less well attached to the ear,fall to the ground. And those were the ones that will germinate, ensuring the next harvest. In this way, an evolutionary process took place, anthropic but involuntary, which favored plants with less well-adherent grains.

This changed when humans finally learned how to sow. Then those people took the harvest home where they threshed it, separating the grain from the straw, and allocated part of the harvest to consumption and another part to the next planting. This new sowing was done with grains firmly attached to the spike, which could only be separated by threshing.

Unconscious anthropic evolution then changed direction, favoring spikes that better held the grain during harvesting, incidentally increasing the harvests´volume. With more abundant harvests the quality of life improved, which had a rapid impact on population growth.

During the first periods, population growth did not present serious problems: the new generations either inherited the family space or looked for free land to settle. But at certain point, when it was already very difficult to find free land nearby, in order to survive young people had only two options, either to migrate away from their parents in search of viable spaces or to engage in banditry.

The second option had to favor the concentration of the population in urban centers suitable for mutual defense against criminal gangs attacks. Cities of some size flourished in the Middle East such as Çatal Höyük, Çayönü, Hacilar (Turkey), Tell Halula (Syria), Jericho (West Bank) and others.

The first option, emigration, generated the expansion and spread of the Neolithic agricultural economy. From the shores of Egypt to those of Anatolia a trickle of small demographic contingents began to migrate, bringing with them a new way of generating resources and living.

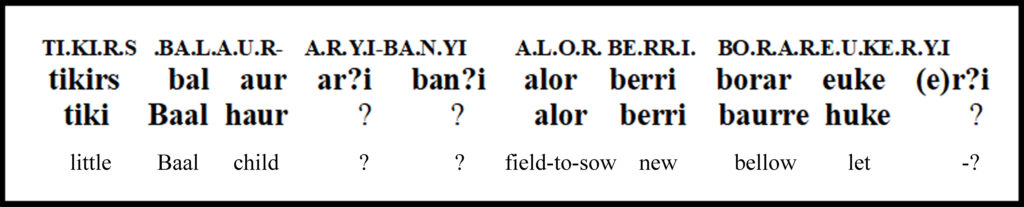

The custom in archeology of baptizing the people of the same lineage with a different name when some of their cultural traits change, has generated in the archaeological literature a large number of different names referring to the same Natufian people: Khiamians ( -10,000 a. -9,500, the first ones to believe in the bull of the sky?), M’lefaatians (-9,500 to -8,500), Mureybetians (-10,000 to -8,000), Sultanians (-9,000 to -7,000), Tahunians (-4,500 to -3,500) and Ghassulians (-4,500 to -3,500)… Different names that disguise a single branch of humanity to which also belonged the cultures of Karim Shahir, Jarmo, Tell Hallaf, Ubaid, Tepe Gawra, Uruk and, already reaching the around the year -3,500, we can talk about protoliterary Sumer and then historical Sumer.

This branch of humanity that has been denied a name and that has been concealed under an avalanche of unrelated names, took the lead in very brilliant and transcendent historical processes that at certain point generated phenomena such as the neolithization of Mediterranean Europe, and later Western European megalithism, Stonehenge and Iberian epigraphy, but it is necessary to explain how this process took place.

FOLLOWING THE DAILY PATH OF THE SUN

We know that even before they learned to make pottery, during the PPN (Pre Pottery Neolithic or Aceramic Neolithic) they already knew how to navigate very effectively, because they had colonized the island of Cyprus, separated by about 70 km from seaward closest point to the continent, the southern coast of Anatolia. In Cyprus they lived in villages such as Klimonas and Khoirokoitia (or Khirokitia) where they grew cereals, raised goats and sheeps and hunted a small wild boar and a dwarf hippo endemic to the island.

The spread of vector of neolithization populations continued along the northern and southern of the Mediterranean shores, and this is the cause of some cultural and linguistic features that bring the Imazighen closer to the Basques and which have often caused astonishment in some authors.

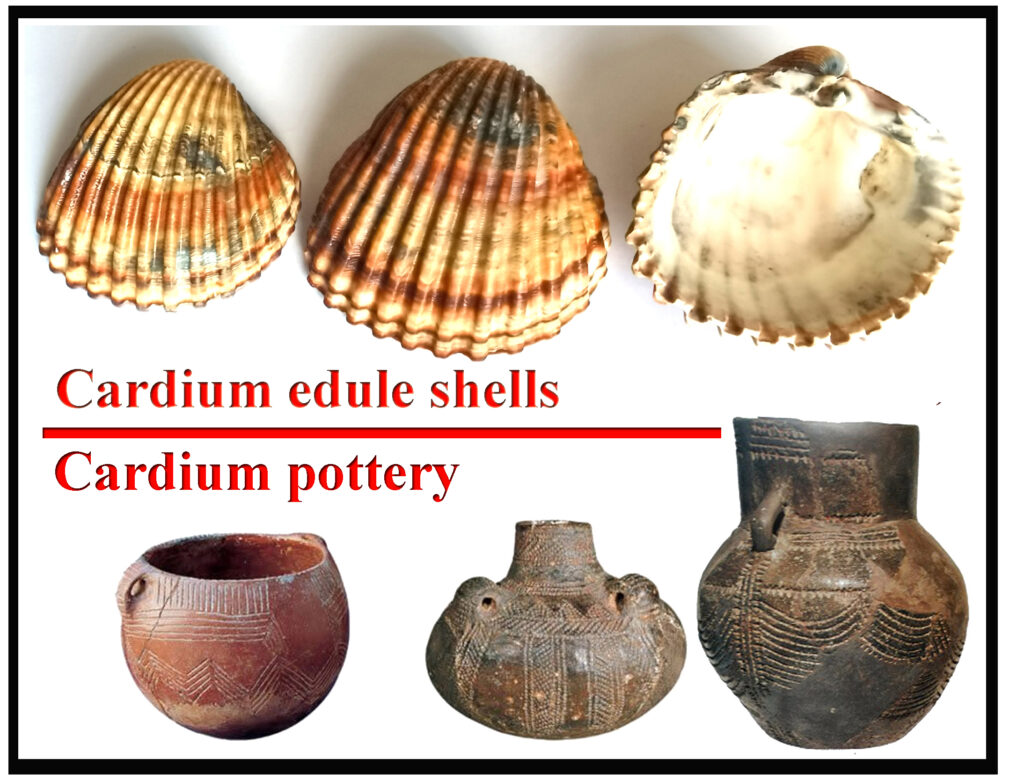

Along the northern shore, the agricultural settlers of the Early Neolithic (EN) passed to Greece where they generated the civilization we know under the names of pre-Sesklo, proto-Sesklo and Sesklo. Through the Ionian Islands and the Adriatic Sea they reached the Italian Peninsula, later the Gulfs of Genoa and Leon, and finally the Iberian Peninsula.

From the Adriatic Sea shores to the Valencian Country, a very characteristic EN pottery is a vestige of the civilization that has been called the Impressed-Cardium complex because of the decoration that many of its wares present. With the paste still raw, they pressed (“printed”) on the outer surface many marks made with nails, fingers, a spout, etc. (printed pottery, on the eastern coasts) or with the edge of a cardium edule (Cerastoderma edule) which we know as cardial pottery, abundant on the westernmost coasts.

The more or less unconscious offensive that Indo-Europeanism has launched against the peoples prior to the Aryan invasions has also manifested itself in the denial of a cultural unity for the Mediterranean coastal peoples. Some authors refuse to speak of Impressed-Cardium culture and prefer to speak of different cultures such as those of Molfetta (southern Italy) or Stentinello (Sicily) and adduce obscure genetic studies, based only on a few individuals, in order to draw bold conclusions that sometimes defy common sense.

Although in each region the cultural changes may occur with some chronological differences, broadly we can say that the EN in Western Europe lasted from -5,500 to -3,000. Pottery, a vestige that endures through the centuries and allows archaeologists to establish chronological sequences and cultural differentiations, in the Middle Neolithic (MN) experienced a logical evolution, both because of the fatigue of the “fashionable” model such as the fact that the terrain was getting to be better known each time and better clays were found by penetrating the interior of the earth and learning how to bake the pots better.

So, with a noticeable uniformity, pans with a smooth and undecorated surface appeared everywhere, and with better quality pastes than the Cardium pottery ones. In all probability the people remained the same, so the descendants of the Natufians and their Anatolian relatives. They probably spoke languages closely related to each other, with the logical dialectal facies that 25 centuries of existence in separate regions had generated.

In archeology this relative uniformity of the MN has not been included in the nomenclature and each cultural facies of each region has been given a different name. Thus in Italy we speak of Lagozza culture, in Switzerland Cortaillod, Michelsberg in Germany, the Czech Republic and Austria, Chassey in France, in Catalonia Sepulcres de Fossa, in Spain Culture of Almeria, and in England Windmill Hill culture to which, by the way, the builders of Stonehenge belonged.

The descendants of the farming pioneers of the Near East did not stop once the Mediterranean shores colonized. Already through the Rhône, Saône, Loire and Seine valleys, they had reached the Atlantic, and probably also through the Strait of Gibraltar. Even if they had not reached the British Isles during the Impresso-Cardial pottery period, the Windmill Hill culture shows us that they had already taken root there during the MN.

With the understandable diversity caused by temporal and geographical distances, the people of Windmill Hill had much in common with the rest of the MN populations descended from the ancient Cardial EN settlers, themselves descendants of the Natufian population. The information we obtain from any of them must be considerably applicable to the rest, although not in an absolute and uncritical way.

INDOEUROPEANS OR ARYANS

Don’t be surprised that he often refuses to use the term “Indo-European” to designate a people who were not originally from either India or Europe, since they arrived in both places as invaders.

The nomenclature “Aryans”, with such painful political connotations in the middle of the 20th century, is shorter and illustrates very well the overbearing character of this branch of humanity, which in India reduced the native population to untouchable Dalit pariahs, in Sparta they enslaved the natives turning them into helots, in classical Rome the patricians oppressed the plebeians -especially before the latter marched to the Sacer Mons- and in the Spanish state they imposed themselves on the Iberians descendants (Basques and Catalans latu sensu) forbidding their languages for centuries and imposing their monarchy and their laws.

Regardless of the Natufians descendants expansion, in the Pontic steppe, that is to say, from the north of the Black Sea to the north of the Caspian Sea, the remains of nomadic tribes and herders of large tribal herds have been found.

Archeology has named the vestiges left by those populations as the Samara culture (from -5,200 to -4,800) which must have given rise to other manifestations such as the later cultures of Khvalynsk (from -4,800 to -3,800) and Sredny Stog (from – 4,200 to -3,500), the latter already a little more towards the west and towards the south.

Everything suggests that these Aryan people, bordering the northern and then the western shores of the Black Sea, reached the delta of the Danube river, through whose valley they penetrated towards the heart of Central Europe where they must arrived a few centuries later than populations from the Mediterranean.

MEGALITHS

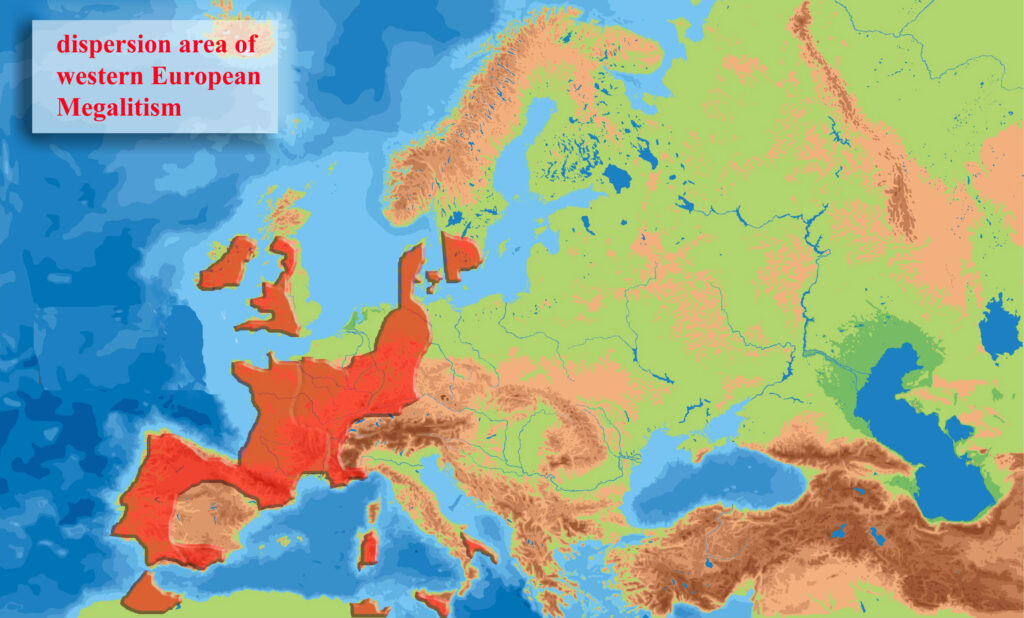

During the MN a cultural phenomenon, that has become very famous nowadays, appears: the megalithism. First the menhirs and shortly afterwards the dolmens occupy a large part of the territories colonized by the descendants of the pioneer Neolithic farmers who had spread across the Mediterranean, whom from now on, I will call Riversiders.

It must be said that in the lower Danube valley the megaliths are absent, as was the case with the Cardial pottery, making the difference between the Mediterranean Riversider populations and the Danubian ones more obvious and invalidating Colin Renfrew’s theses.

LATE NEOLITHIC AND CHALCOLITHIC

Towards the year -3,500 important changes had already taken place in the populations that occupied Western Europe. EN pionners descendant societies had consolidated and long-range trade routes existed. Archaeological excavations have unearthed, for example, amber jewels originating from the Baltic Sea and brought to the Mediterranean by fairly regularly established routes.

The Late Neolithic chronology and that of the following period, the Chalcolithic overlap according to some authors, but we can place them between -3,200 and -1,800.

A very interesting vestige has come down to us from the Chalcolithic, the frozen and mummified corpse of a man from around the year -3000, killed in a glacier in the Alps. The dresses, the footwear, the leather bag, a bow and arrows, a copper ax and a flint dagger are preserved. We know his diet, his pathologies, his tattoos, his place of origin and many other very useful data for the knowledge of that period. We even gave him a name (no doubt quite different from what he actually had): Ötzi.

The most characteristic phenomenon of the Chalcolithic period is undoubtedly the Bell Beaker culture. These are often profusely decorated earthenware vessels and many of them have an inverted bell shape, with the mouth upwards turned. Their shape makes them suitable for being able to hold them with two sticks, without burning even if they are hot. Burials in which they appear bell-shaped beakers also often have objects such as V-pierced buttons, archer’s protective armlets, triangular copper daggers, and sometimes stone or gold necklace beads.

The emergence of the Bell Beaker culture does not imply the arrival of new populations or, even less, the disappearance of previous populations. At a certain point it was considered that the Bell Beakers were a kind of copper smelters, nomads, who traveled the world in search of broken utensils to remelt and make new utensils or weapons with, but we have no indisputable evidence it was not the same indigenous farmers who learned the new metallurgical technique.

In any case, one thing is clear: England still followed the European way of life of Mediterranean origin, while Danubian Europe did not know the Bell Beaker culture except in the most western areas, Hungary upstream.

Even newer metallurgical technique when humans learned to alloy tin with copper, and obtain bronze, much harder and more suitable for tools and weapons; the process was still casting and molds.

And even more novelty when we learned the first rudiments of iron and steel industry from minerals that melt at very high temperatures, unattainable in those times. With hammer blows on the red-hot mineral, the ore was purified and then, also by hammering, the desired utensil had to be shaped. It’s what we call “wrought iron”.

Through these ages many aspects of culture changed relatively little. If we consider the long duration of Christianity in times with so many changes in material culture as the last twenty centuries, it must be assumed that beliefs and mythologies evolve more slowly than other aspects of life.

What today we call Carnival, the festival of debauchery at the winter solstice, in all probability it must have lasted many millennia. Let’s see what we know about Carnival.

THE DEBAUCHERY FESTIVAL

Most likely the desirability of taking advantage of the days of the year when there are fewer agricultural occupations to enjoy and compensate for the harshness of existence was already known after a few centuries of the EN. Unfortunately writing was still unknown and we have not received any textual information on this subject.

As I have already said, the vegetation´s decay observation from the autumn and the recovery from the spring, surely had to give rise to the idea of the resurrection that would later appear so often in different mythologies.

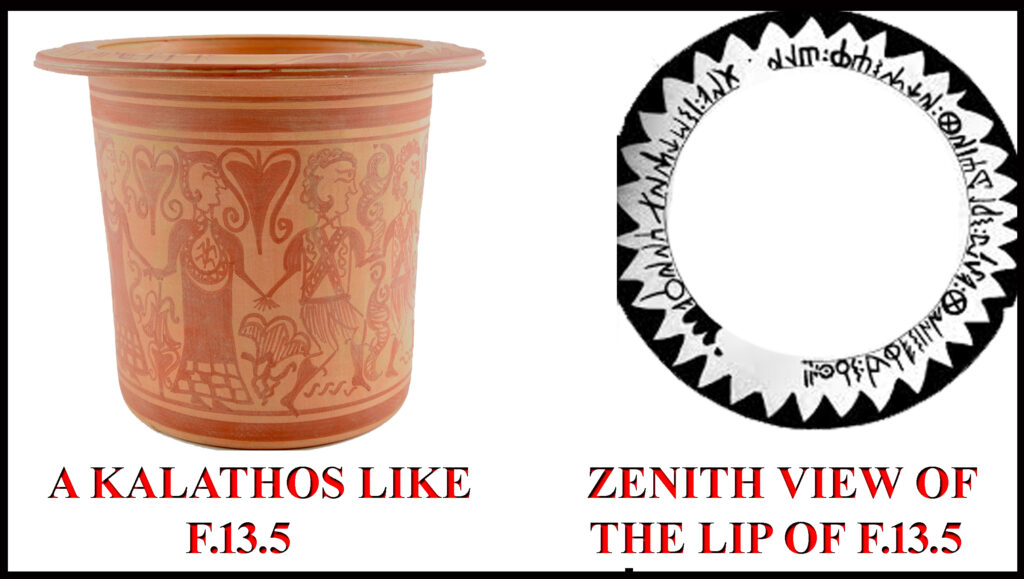

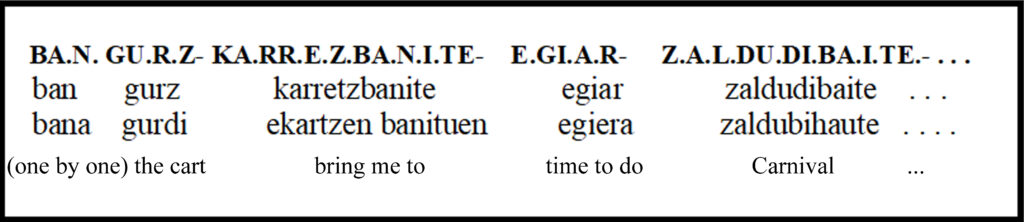

All the indications point to the fact that the MN people, descendants of first colonial farmers of the EN came generations earlier from the Middle East, would have already known Carnival from their distant origins, although probably with variants both in the rituals and in the denomination: from the Sumerian Akitum, celebration of the beginning of the year, in spring, to the Iberian ZALDUDIBAITE (the Basque zaldubihaute) that the Llíria´s kalatos edge show us, collected in the Monumenta Linguarum Hispanicarum (M.L.H.) by Jürgen Untermann with a F.13.5.

The Zaldudibaite, which in many places was the winter solstice festival, celebrated the rebirth of life after the winter period when the sun had lowered below the horizon and most of the vegetation had died.

As we already mentioned, a simple stick or rock planted on the ground as a gnomon made it possible to know when the shadows stopped lengthening and the sun began its slow ascent over the horizon to give way to the vernal and summer warmth. And, consequently, to know which day is the solstice: just by drawing the shadows cast by the stick on the ground and then looking for the central day of the five or seven ones in which the shadow is longest (winter solstice) or shortest (summer solstice).

An available “technology” to the most primitive populations in the EN. When the shadow begins to shorten, the daytime become noticeably longer and the grass and plant life begin to renew a new cycle every year.

I think we will never know how long it tooks humans to relate the plant cycle to the solar cycle, but I it must be assumed that just a little while.

It is very likely that even if at first the festival was celebrated in spring when the vegetation revival was noticeable, later discovery of the winter solstice when the day reaches the minimum duration and the sun is at its lowest on the horizon, from when the recovery began, the solstice was the choosen date.

The first written news that we have of this festival is the Sumerian Akitum. Despite being so relatively recent, since the writing appears around -3,300, it is not a solstice festival but a spring one. It was so important that it was documented in the most famous and ancient narrative, Bilgamesh or Gilgamesh.

In the celestial bull adventure, Bilgamesh, fifth king of Uruk (Unug in Sumerian), son of the “lady of the wild cows” Ninsun, offends the goddess Inanna by rejecting her love. Hence this one gets that An, the god of rain and vegetation, principal among the gods, sends against him the “celestial Bull”.

Bilgamesh, with his friend Enkidu fight the bull and defeat it. Interestingly, before leaving for battle, Bilgamesh tells his mother not to worry, that he will be back “before Akitum“, that is, he won’t miss the festival.

THE IBERIAN EPIGRAPHY

Let us first reflect on some methodological errors that have distorted the problem of the correct understanding of the Iberian inscriptions, making success in their interpretation just impossible.

1st error

With a worrying lack of vision, many Spanish academics are still of the opinion that every Iberian word written on the famous Ascoli bronze is an anthroponym. Based on this and leaving aside the fact that primitive societies usually attribute to their individuals proper names taken from vocabulary of common names (especially before what some authors call the “onomastic revolution” of the Late Middle Ages), and starting from the tacit idea that the Iberians had official names in the style of the Roman tria nomina, they devote their time and energy making long lists of supposed onomastic formants and of personennamen, where they include at will and without the slightest logical justification both verbs and adjectives, pronouns, etc…

Of course, nothing prevents you from “baptizing” a baby with names like “cut-the-twig” or “as-there-is-god”. In fact any part of the sentence, prepositions and conjunctions included, could serve as anthroponyms, but if we adopt this criterion, the famous Popperian falsification has no place, removing all scientific character from the hypothesis.

The mistake, simply and directly explained, is like, in case the Hunkappa Lakotes Sioux had known the writing and inscribed on a stele the name of their great leader Tatanka Iyotake (Sitting Bull in English), the white researchers whenever they read tatanka (bison) or Iyotake (sit), interpreted it as an anthroponym, as if Amerindians could never speak of a bison or sitting.

Obviously, such an erroneous methodology explains why, a century after the Iberian semi-syllabary was deciphered, Spanish academics still continue saying that the Iberian language “could not be deciphered” and that “it does not have a clear relationship with Basque”.

Pas besoin d’être Jérémie to guess the future of this subject: either our lauded academics abandon this obsessive idea about onomastics, or centuries will pass without understanding the epigraphs.

2nd error

I do not intend to say that the Spanish state political situation had influenced our academic Iberianists, but coincidentally, the majority position of denying the intimate relationship between the Iberian language and Basque is perfectly in line with the mistrust that Castilian centralism feels towards Basque separatism. The opinion that “Iberic cannot be understood through Basque, we will have to wait for the discovery of some stone from Rosseta ibérica” has sterilized Iberian studies.

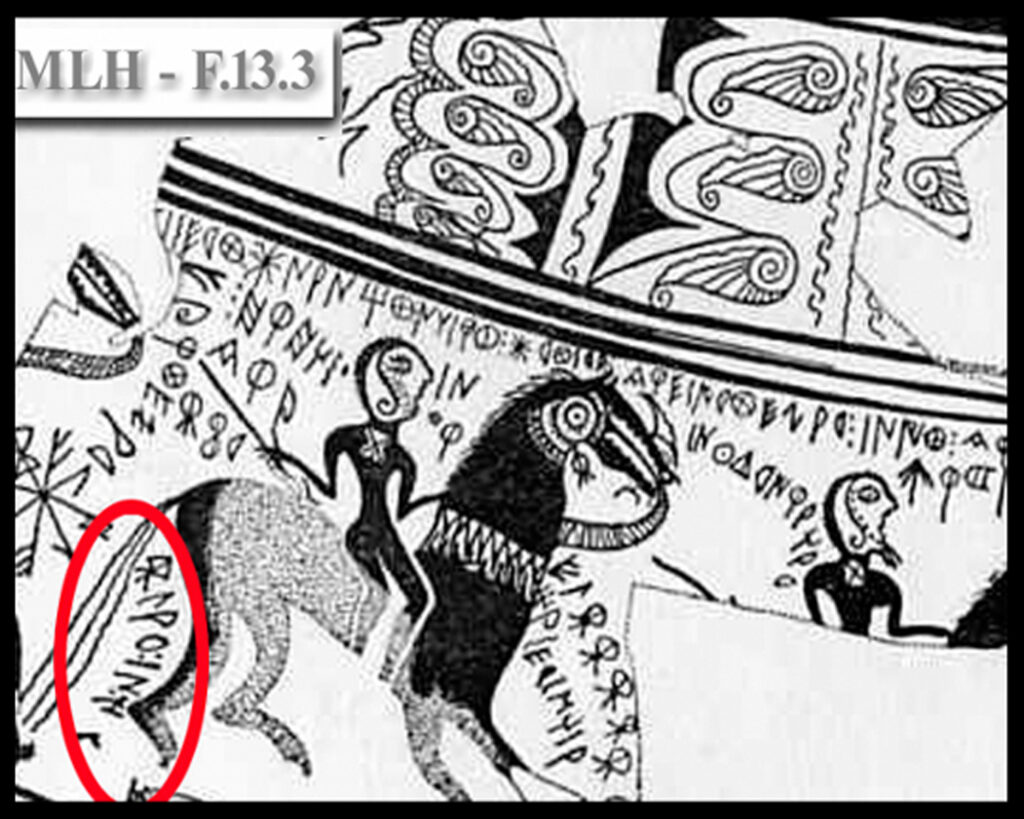

When I wanted to convince a friend that Basque is Iberian evolved over the course of two millennia, I went to the so-called “Library Jar”, that is to say the one collected in the Monumenta Linguarum Hispanicarum (M.L.H.) with the reference F.13.3

In addition, this tall pot painted with scenes that have often been considered warlike, will also serve to combat the great tendency of our researchers to consider the vestiges of the ancient world as a set of temples, palaces and fortifications, despising aspects less “heroic” in history, such as the market places or, for example, the humorous scenes.

We note the complete absence of weapons on the horsemen. It should make us think… war or, better, festive parade?

It´s about the inscription painted just below the horse´s anus and written vertically as if it were falling to the ground…

Unterman’s transcription, correct as all his transcriptions tend to be, is belar.ban.ir [... , considering that this ir could be part of an unfinished or eroded word.

What is really of capital importance is the situation of the legend in question, which as we can see in the attached image, seems to fall to the ground as if it were the natural product of the daily metabolism of such a noble horse.

Here is a “rare coincidence”, in Basque the phrase belarra ban(atu) means “grass to distribute”. Grass which, in this case, we assume is distributed “after being duly digested”.

The fragment ir could correspond to the word irte = exit, making it clear that the herb to be distributed comes from that part of the anatomy, the mention of which is often considered in bad taste.

To summarize: the Iberian language is much closer to modern Basque than the supporters of what I usually call the “onomastological school” seem willing to accept, who firmly believe that the Iberians, like the Romans, were patriarchs obsessed with perpetuating their “glorious” anthroponyms or the respective cursus honorum.

It seems that the temperament of our Iberian ancestors was much less patriarchal and more humorous, more casual and much less epic than some authors have tried to make us believe.

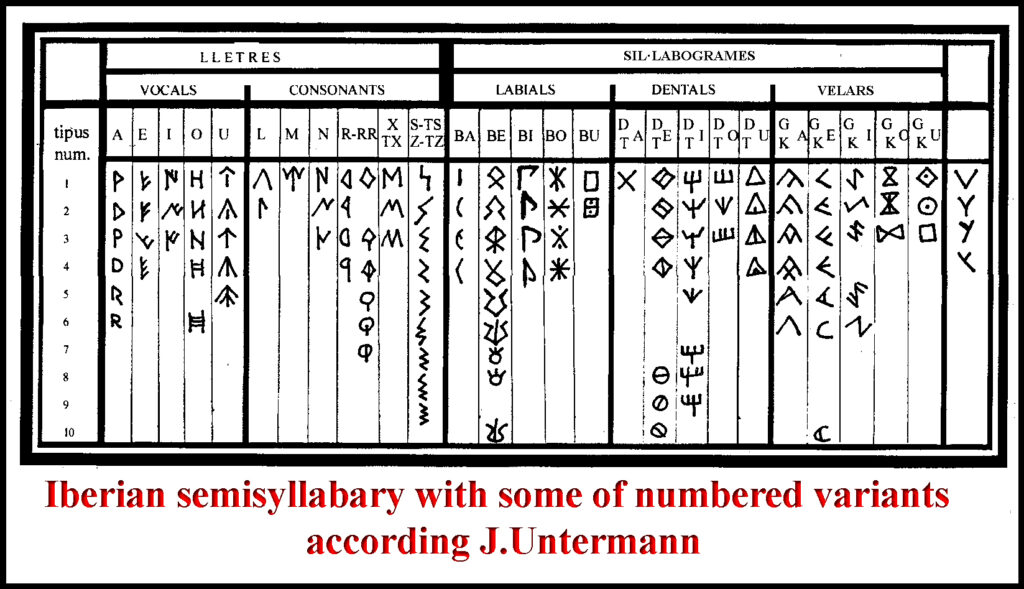

3rd. error

When most current authors transcribe the Iberian inscriptions, when dealing with occlusive consonants they go to always choose the voiceless, strong option. In the velars they never usually transcribe the g, but always the k; in the alveolars never the d, but always the t. Only in bilabials do they always use the sonorous and weak b, given that in the Serreta d’Alcoi lead (M.L.H.-G.1.1) written in the Iberian language but in the Ionic alphabet, no letter pi appears, but always beta.

I do not intend to discuss the reasoning on which this preference is based, even though I do not share this usual systematic devoicing of velars and dentals, above all because when comparing the Iberian inscriptions with the Basque lexicon, it produces a tremendously sterilizing effect.

I can affirm that if we wish to understand the meaning of their inscriptions (and this is my objective, and not deepen the knowledge of the sounds and phonemes in the Iberians speech), even if it were true that they did not use voiced occlusives , we must bear in mind that, whether due to processes of lenition, sonorization or fricatization unknown by me, in the transition from Iberian to the current Basque, many of these consonants may have changed over the centuries.

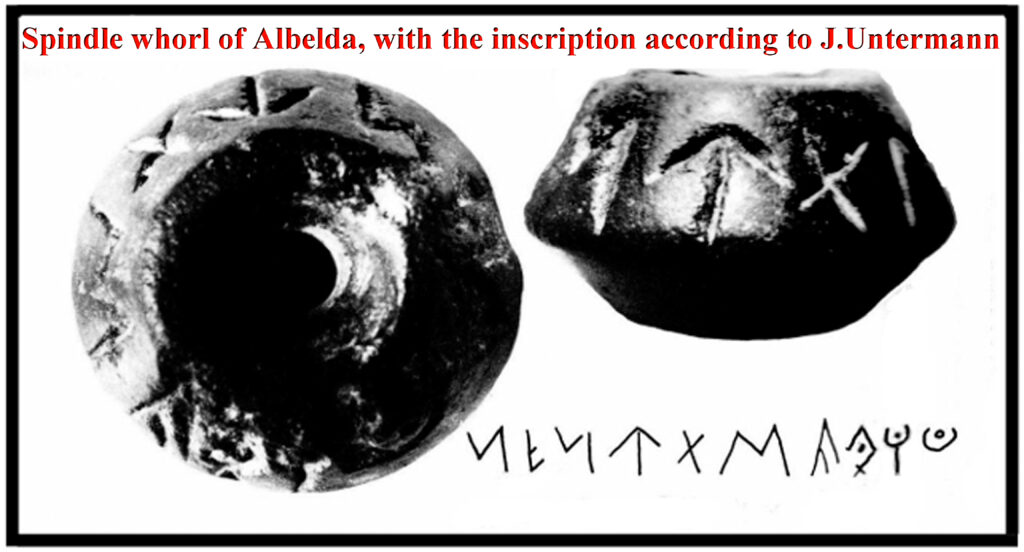

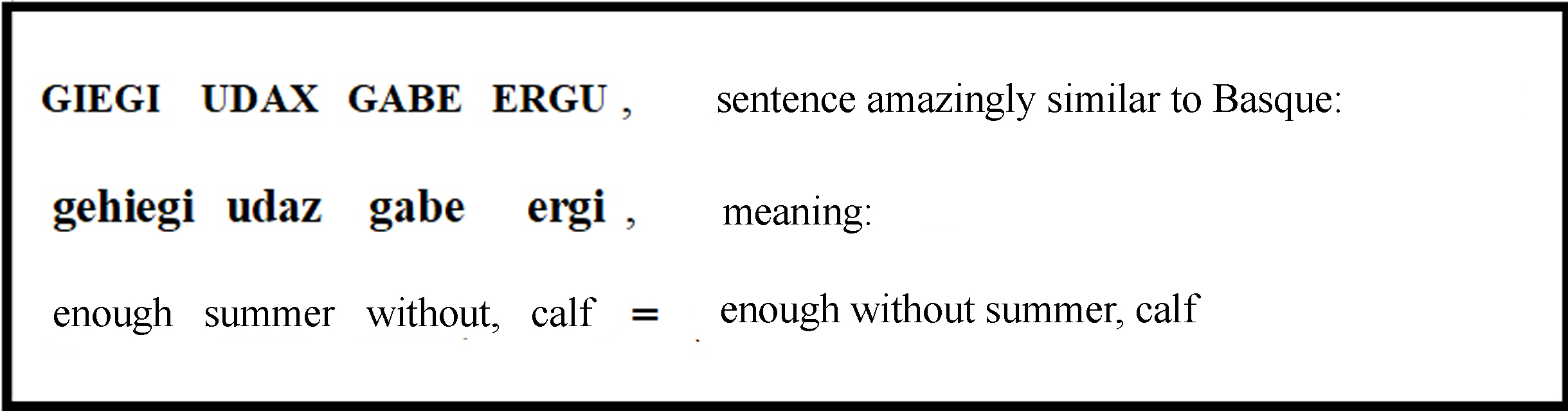

The clearest, even most poignant example I know is that of the spindle whorl found in the Castellassos acropolis in Albelda (Huesca), serialized as D.11.3 in the M.L.H., Monumenta Linguarum Hispanicarum by Untermann, and shown here in the original image of the autor himself:

Demonstrating his skills as a transcriber, Untermann interprets the last three signs as BE, R and KGU, giving us as the final transcription kulmutas’kaberku, an expression which, as is obvious and notorious, bears not the remotest resemblance to any phrase or any Basque word.

Knowing the ambiguity mentioned in the first paragraph about the velar and alveolar occlusives, a minimum of prudence requires us to find a notation that allows us the possibility of interpreting the signs with the two options, unvoiced and voiced, something like this: GKI.E.GKI.U.DTA.tX .GKA.BE.R.KGU, as a basis on which to work forging our hermeneusis.

Further work will show us that, unfortunately, all stops in Untermann’s transcription should be voiced and not unvoiced. And that the character of the inscription will become relatively easy to understand if we change these consonants, being:

GIEGIUDAXGABERGU

The problem of segmentation, given that the inscription does not have separating punctuation (interpunctions), will be greatly simplified if we consider that in Basque, there are the words gehiegi = enough, sufficient, very coinciding with the GIEGI of the first 3 signs, and gabe = without, this last one exactly the same as in the inscription, remembering that according to the Basque syntax, gabe must be placed after the word it refers to.

GIEGIUDAXGABERGU

…and considering that the unpronounceability of RGU and the last gabe´s vowel suggest a haplographic phenomenon, with the elision of an initial E, we will finally have:

We note that the fact that gabe = without is placed after the word it refers to, so uda = summer, agrees 100% with the syntactic rules of current Basque. Regarding the change from ERGU to ergi, many indications suggest that the Iberians pronounced the u like the French one or like the German one with a diaeresis, ü.

It can be objected that the phrase has, apparently, no meaning … unless we remember the so-called cycle of Bel, a seasonal myth explaining the eternal cycle of the seasons of the year succession, which narrates the struggle of the god of storms, rain, vegetation and renewal, the calf Bel, against the old bull Mot, god of disorder, cold, winter and death.

At one point, during the inclement weather of the peak of the cold, Mot is about to permanently eliminate Bel, causing an eternal winter to reign over the lands. That is why the humans, fed up with the rigors of winter, ask the calf Bel to react and defeat Mot, to bring back the vernal rebirth of vegetation, because “it’s enough without summer”.

May Bel make the cold of Mot die, as it will end up doing year after year, at the end of winter, the time of the celebration of the great ancient festival, what nowadays we call Carnival.

In my opinion, the Bel cycle, rooting its origins at least in the ancient Neolithic, perhaps in the ceramic PPN or who knows if in the middle of the Mesolithic, must have reached the west not with the Fenopunic Semites, but probably much earlier, with the first agricultural settlers of the EN. And it constituted the mythical basis of the greatest festivity of that time, the festival of the fertility, the renewal and the vegetation and nature resurrection, the Carnival, the debauched party that gave those hard-working farmers a necessary illusion to continue wanting to live, despite the difficulty imposed by the precarious conditions of primitive life.

The Bal or Bel importance in antiquity is reflected in the Judaism and Christianity efforts to demonize him. Let’s remember some demon names like Luzbel, Beelzebub, Belial, Belphegor… or the one of the perfidious (according to the Bible) queen of Israel Jezebel. On the contrary, the pagans deified Bel in theonyms such as Belenos, Belisama, Belona, Balor, Balder or the supposedly Celtic festival Beltane (which, by the way, is also called nowadays Belsua by the pagans, that is, “Bel´s bonfire” in Basque).

Seeing the Bel´s degree of implantation in ancient societies, we should not be surprised that the Iberian epigraphy often mentions it explicitly or implicitly. The god’s name can be found on the spindle whorl serialized in the M.L.H. like C.4.2 and found at the El Castell site, in Palamós, which we will see below.

I will separate each Iberian grapheme with a period, and I will represent the separating interpunctions with a dash. The interpretation of each word I refer to the Hiztegia Bimila by Xabier Kintana (A.G. Elkar S.Coop. Bilbao 1988) because it is the dictionary with more archaisms I have.

In the tables you will see from now, the first line is the iberian signs transliteration. The second line is the same text but segmented. And the third one, in lowercase, is the current Basque word.

I transcribe the disputed Y-shaped sign as it is, without any phonetic value:

Huke is the auxiliary zer-nork = “what-who” that is, with ergative subject (of active transitive sentence but without indirect complement nori) in 2nd person hik-hura = you to him, in indikatibozko baldintza, a form of conditional. Applied to baurre it would mean “you would roar him”. We do not know to whom, and we will not know it until we discover if the fateful sign Y is a voiced bilabial nasal, as some authors have intended, or some other consonant.

M.L.H.- F.13.5 Kalathos of Llíria (Llíria 3 by D.Fletcher)

M.L.H.- F.13.5 Kalathos of Llíria (Llíria 3 for D.Fletcher)

Of the 49 signs or graphemes preserved on the lip of this “top hat”, we will focus on the first 25.

The similarity between the names of the Iberian and Basque Carnivals is obvious. But this is not the only argument in favor of the “carnivalesque” interpretation. Let’s see other inscriptions.

EXTRATERRITORIALITY?

It must be said that according to the testimony of a coetaneous, Sulpicius Severus, who lived in Gaul between the 4th and 5th centuries, the Celtic language and the Gallic one are two different languages.

In “Sulpice Sévère témoin de la communication orale en latin à la fin du IVe siècle gallo-romain” by Jacques Fontaine 1993, page 29, Postumianus says:

…”Dis donc”, dit Postumianus, “parle en celtique ou, si tu préfères, en gaulois, pourvu que tu nous parles de Martin…” (“…speak in Celtic or, if you prefer, in Gaulish, as long as you talk about Martin…”).

According to Franck Bourdier, who was laboratory director of the École Pratique des Hautes Etudes, the Gallic language had to be different from the Celtic one and very close to Basque (Préhistoire de France. Flammarion, 1969, pp 364-373).

Pierre Yves Lambert’s work “La langue gauloise” (Ed.Errance, Paris 1977) can be found in a context of so much uncertainty about the identities of Celts and Gauls. In it, among other texts, some spindle whorls are analyzed that confirm my opinion on Untermann’s interpretation of Valls’ fusaiola (“La lengua ibérica, nuestro conocimiento y tareas futuras” Veleia 12, Gasteiz 1995) that he interpreted as “Sinekunsir made it for Ustanatar” or “Ustanatar made it for Sinekunsir”, and that it seemed impossible to me that a so simple and cheap object as a spindle whorl deserved such a solemn dedication.

Indeed, according to Lambert, those found in Gaul and written in a mixture of Gaulish and Latin, exhibit much more modest inscriptions: “Ave domina sitiio” which he translates as “hello Lady, I am thirsty”; “Nata vimpi curmi da” (pretty girl, give us beer); “taurina vimpi” (beautiful calf), expressions that we will discuss later, in order to see how they coincide in being interpretable from the perspective of the old Carnival.

But the inscription that most shocked, struck and puzzled me was the one found on a spindle whorl in Autun. Located between the basins of the Loire and the Rhone in an area of good passage between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, on the “amber route” (or very close) that had been operating for many centuries, the current city of Autun (Saône et Loire) has, about 20 km to the west, the remains of the ancient Bibractis, mentioned by Cesar. These places are therefore outside the scope traditionally considered Iberian, in territory that is usually considered Gallic or Celtic. The inscription reads:

MATTADAGOMOTABALINEENATA

Nevertheless I´m not persuaded by this interpretation. Following W. Meid, Lambert proposes MATTA = girl, as in Raetho-Romance, and, to a lesser degree of probability, NEE NATA = spin the threads, interpretation maybe influenced by the fact that the support is a spindle whorl, especially because the only similarity that can be welcomed for NATA is the Breton neud-en = thread, which only have in common the voiced alveolar nasal consonant and the alveolar in one case voiced and in the other voiceless .

He also suggests another possibility: BALINE as the Latin balneae = baths, and NATA = girl, stating that the mixtures of Latin with Gaul or Celtic were common at that time. It refrains from giving any interpretation of the entire text.

Two things suddenly struck me: firstly the existence, together in such a short sentence, of MOT and BAL. Secondly, that DAGO is still today for the Basques, the third person singular of the verb egon = to be. Seeing this, I segmented the registration like this:

MATTA DAGO MOTA BALINE E NATA

In Catalan and Spanish, languages that geographically coincide with Iberian, matar means to kill, to take life. In Basque mataka means to fight violently (-ka suffix of insistence, of continuity), so it didn’t seem like a fantasy to think that in Gaul or Iberian it meant the same thing.

Regarding MOTA it should be remembered that currently -a is the determining suffix in the Basque language, although according to Michelena the old determining would be -r.

BALINE could probably be a diminutive of BAL, as it is a young calf.

Finally, regarding E NATA, Latin would indeed have been used as Lambert says, and it would mean “is born”. Now let’s see the consistency of the resulting sentence:

killed is Mot, little Bal is born

Precisely this is the quintessential summary of ZALDUDIBAITE, the death of winter (Mot) and the birth of good weather (Bal). Obviously, imagining that it is nothing more than an improbable coincidence is quite difficult to believe if we want to stay within the limits of scientific rationality.

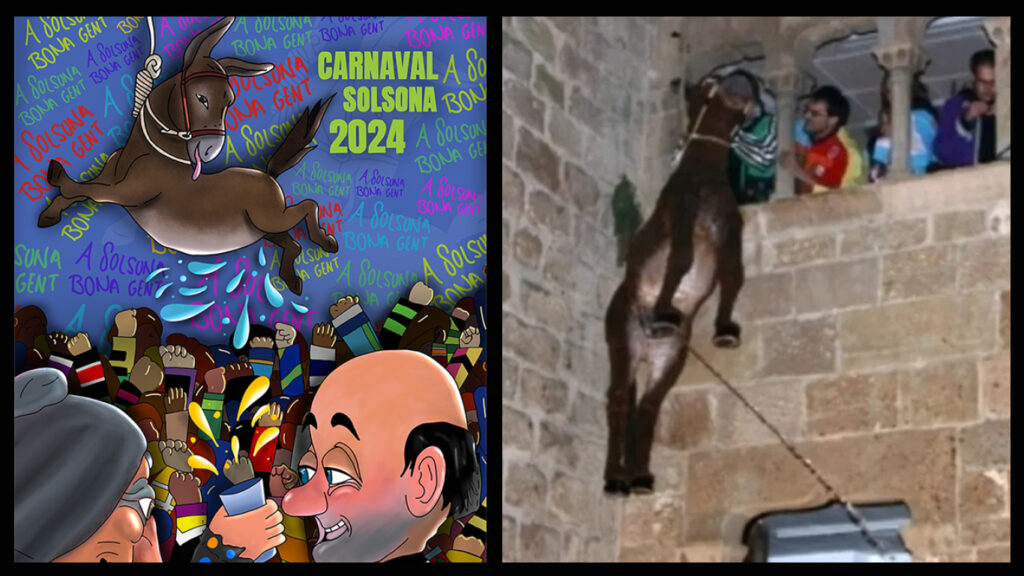

The inscription on spindle whorl ave domina sitiio = hello lady, I’m thirsty, and the one that says nata vimpi curmi da = beautiful girl give us beer (always following Yves Lambert’s interpretation) perfectly match the carnivalesque theme, and both coincide to make fun of the castrated bull’s lack of masculinity and to express the request that he offer his excreta to the present audience, in the manner of the hanging cloth donkey of the Solsona Carnival (Catalonia).

The inscription taurina vimpi = beautiful calf, would only refer to the first mentioned aspect.

Carnival of Solsona

RITUAL CASTRATION, SOME SPINDLE WHORLS AND TWO LEADS

It is difficult to know how the Ancient Carnival celebration took place in Stonehenge and Carnac, because we do not have any document that reveals it directly to us, but we can rightly think that despite the distance in space and time with the Carnival of the Iberians, despite the differences that could exist, the essence of the celebration of the Ancient Carnival might be almost the same.

The Iberian epigraphy, although it does not tell us anything about the relations between different peoples nor the worldview nor the imago mundi of the Iberians, what it does instruct us quite completely is about the celebration of the Carnival that they called ZALDUDIBAITE. No inscription informs us completely, but if we add a little here and a little there, we can get a pretty complete idea.

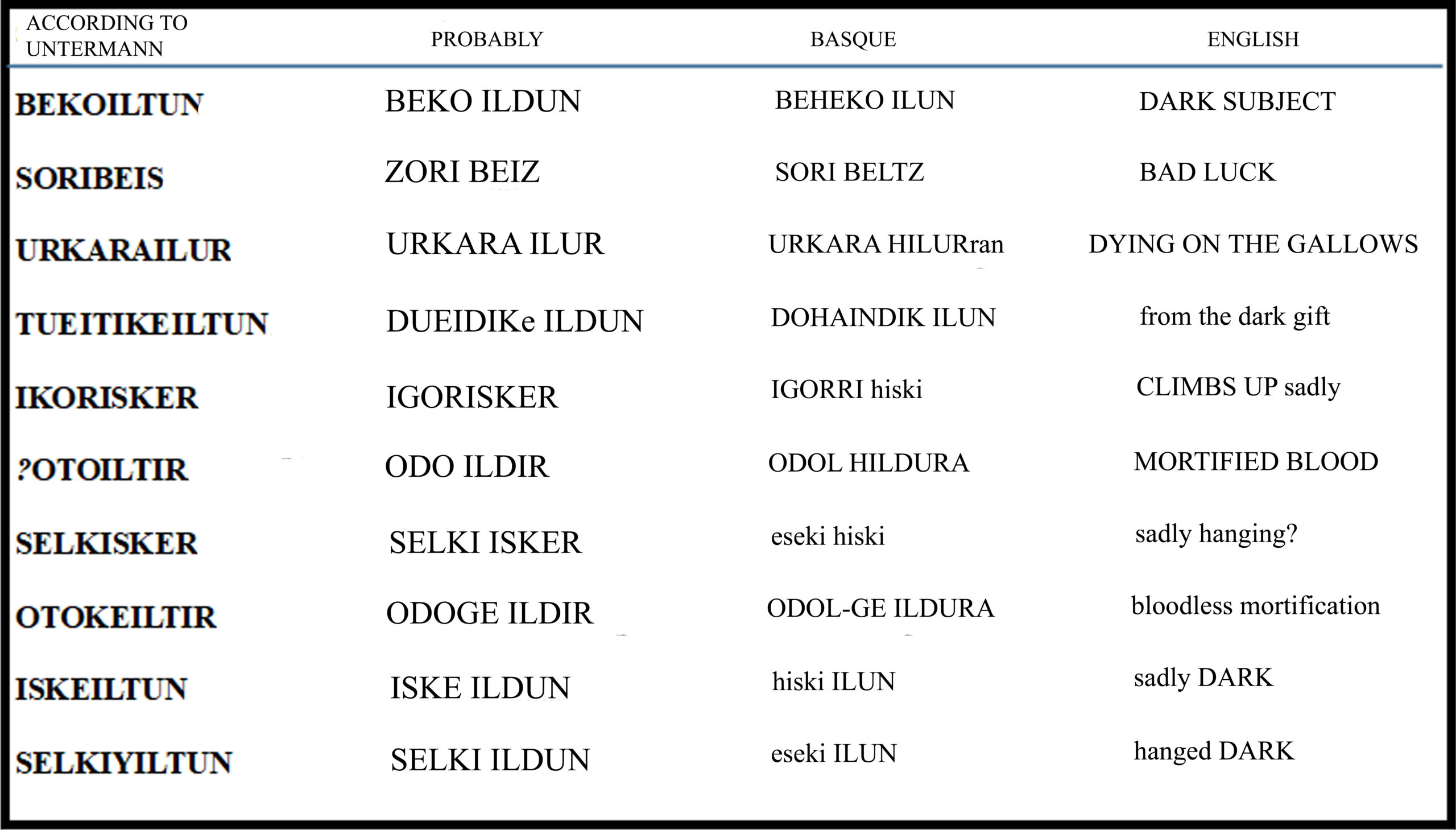

Let’s start with the apparently enigmatic Valls spindle whorl, which is not serialized in the MLH because it was discovered after the publication of the 3 volumes, and which was published by Maria Isabel Panosa (1993) and two years later by J. Untermann (1995).

The inscription, already separating sign by sign, was better interpreted by the two mentioned authors than by some other later attempts. Its 22 signs, once the corrections for unvoiced and voiced occlusives have been applied, say:

U.S’.TA.N.A.DA.R.S’.U.E.GI.A.R.S.I.N.E.GU.N.S.I.R

The grapheme S´ is often used by Iberians to transcribe the equivalent of the Basque notation x or tx. The segmentation was a bit more difficult for me, despite the help of the word EGIAR, one of the most repeated in the Iberian epigraphic repertoire. Lets see the result with, below, a very similar Basque sentence:

UXTAN ADARXU EGIAR SINEGUNSIR

uzta adarxu egiera zinegonzi(ak)

The suffix -xu is still nowadays used by the Basques as a diminutive. The suffix -ak does not seem to be used in Iberian, it currently marks either the plural or the ergative, that is to say, the subject of a transitive sentence. The meaning is, literally:

mowing little horn (or little branch) moment to do the bailiff

That is to say, “(for) the moment of mowing the little horn the bailiff”, or “(for) the moment (when) the bailiff mows (cuts) the little horn”.

It is curious that even today, two thousand three hundred years after this inscription was made, the city hall councilors of the Basque country are still called zinegontzi. It is a clear demonstration that the ancient Ibero-Basque language, after so many millennia of existence, does not need to evolve as quickly as the Aryan languages. If I have preferred the term bailiff to councilor or alderman is due to the influence of Spanish tauromachy, because that is how the person in charge of cutting off the ears of the bulls as a prize for the bullfighters, is called.

Obviously, this sentence raises more questions than explanations. Why should a bailiff mow or cut a little horn or a little branch? The answer will be given by an inscription on lead that will tell us what kind of “little horn” the Valls spindle whorl refers to.

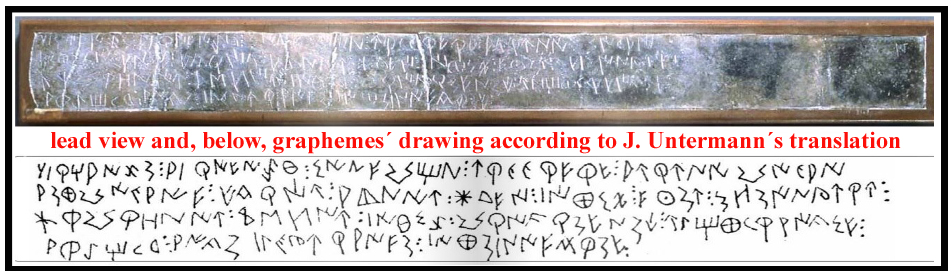

THE LEAD OF “LA SERRETA D’ALCOI”, MLH-G.1.1

This inscription on a lead sheet of about 17 x 6 cm was found in 1921 by the Valencian archaeologist Camil Visedo Moltó. It is written in a variety of the Ionic alphabet very close to the later Latin alphabet and which is easily legible, with the advantage that there is no confusion, in the occlusive consonants, between voiceless and voiced. It must be said that, of the bilabials, in the entire text only appears the voiced B, and not once the voiceless P.

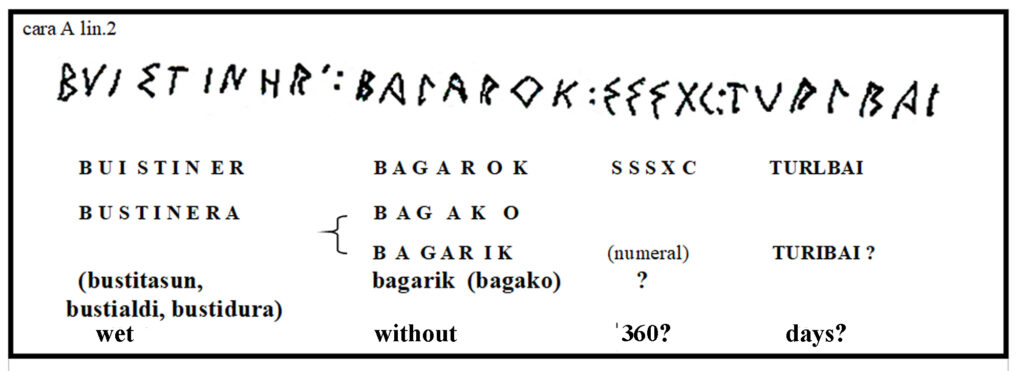

The lead is written on both sides, with 335 letters in total. On side A there are 186 signs from the main inscription, plus 15 from another superimposed inscription (which I will not discuss here), and 133 on side B.

The synecdoche of teeth for mouths is so obvious that does not need to be commented on.

GAROKAN does not appear in any of my hiztegiak (Basque dictionaries), but garo = dew, does. And in the Kintana dictionary there is the form urkan = in search of water. Since water = ur, we must conclude that -kan means “in search”.

DADULA = daudela, being daude the third person plural of the present indicative of the verb egon = to be and -la a subordinating suffix that we will translate as “what”.

BASK, coinciding with the current name of the Euskaldunak (= who speak Euskara, i.e. Basques) is very close to the word batza which nowadays means group, gathering, assembly.

BUSTINER does not exist nowadays, but there are three ways of naming the action and result of getting wet, “the soaking”, all very similar to the Iberian word (cf previous table).

BAGAROK is not used anymore either, but the current forms bagarik and bagako make the meaning of the Iberian word very clear.

The following are five signs that all specialists have considered numerals, with which I agree, but this does not even remotely imply that the character of the lead is commercial, as has been repeatedly stated.

I think one of the biggest mistakes is trying to understand the meaning of the inscriptions based on apparently clear but very debatable clues.

Let’s analyze a little the possibilities of this numeral: if we give sigma the value usually attributed to it in Greece, 200, the total amount exceeds 600, but nothing guarantees us that the Iberians and specifically the author of this inscription followed the Greek canon.

Let’s try another possibility, let´s give sigma the value 100, and let´s attribute X = 50 and C = 10 and we will have 100+100+100+50+10 = 360, that is, the days people would be “without soaking” in case the carnival lasted 5 days. Too much of a coincidence to be due solely to chance.

Regarding TURLBAI, there does not seem to be any equivalence in the Basque language. Common sense tells us that it should mean something like days.

This soaking the author of the inscription seems to long for, could be analogous to the carnivalesque ceremony of the famous donkey´s hanging in Solsona (Catalonia). The animal (for many years made of cloth) has a mechanism that makes it urinate water, thus evoking the typical urination and ejaculation reflexes of the hanged ones. People, below, jump and dance receiving the life-giving “rain”.

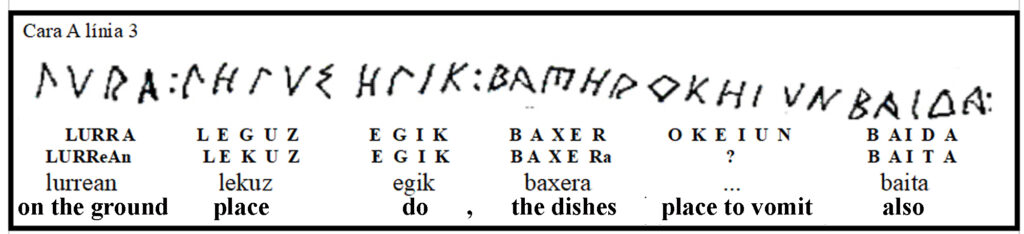

Due to the sentence´s meaning, LURA should be an inessive locative, but currently the Basques would write lurrean, because the suffixed n is the mark of this case.

EGIK is the second person singular of the imperative of the verb EGIN = to do. Let’s remember, however, that in this language the imperative has two genders: if we say “do!” to a man, we say egik, but if we say it to a woman we must say egin. So we know that here the sentence is addressed to a male individual.

Some authors, following J. Coromines, will say BAXER cannot mean baxera (dinner service in Basque) because vaixella (dinner service in Catalan) comes from the Latin vascellum. In my opinion it is the repeated mistake of considering that any etymology that can refer to the Latin language cannot have another previous origin. As if the Central Europeans who arrived in Lazio with an Aryan language, had not been able to adopt any words from the autochtonous inhabitants! The fact of the undeniable total coincidence of the Iberian BAXER and the Basque baxera, reinforced by the coherence of the meaning of the phrase, should make any scientist who doesn´t believe in ghosts reflect.

OKEIUN does not seem to have any equivalent in the current Basque lexicon. We can, however, break it down into OKE, very close to oka = vomit and the suffix -une which applies to a place or a time.

In BAIDA/baita, once again, contradicting the almost unanimous opinion of the Spanish Iberianists, the Iberians used the sonorous dental or alveolar and it has passed to Basque devoiced, voiceless.

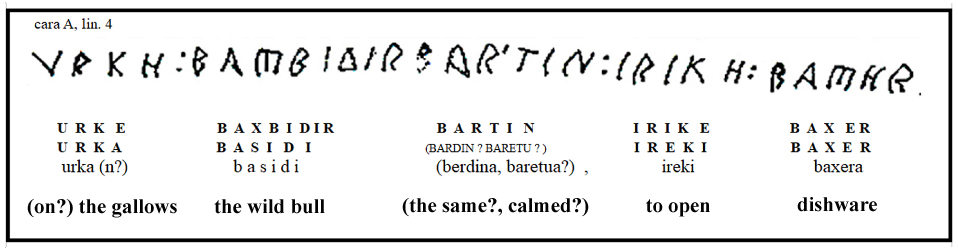

URKE = urka doesn´t need comment.

BAXBIDIR is composed of the prefix basa- or bas- (wild, feral) and idi = ox. That is, an old auroch.

BARTIN has no clear correspondence in Basque. The most approximate form, bardin = berdin = same, does not seem to fit into the context. And baretu, with a voiced bilabial in both languages, a voiced alveolar trill in Iberian but a voiced alveolar tap in Basque, a voiceless alveolar plosive in both languages and with only an alveolar nasal in Iberian, would have a coherent sense but the Basque word is more further away from the Iberian.

TEBIND seems to be the result of a haplography with vowel contraction or elision of an e : TE EBIND -> TEBIND = te ebia = eta ebia = and rain.

The word BELAGASIKAUR is an agglutination of three congruent words, the first two with a very similar meaning, BELAG, like the current belagin or belagile, witch and sorcerer respectively, and ATZI = azti = seer, soothsayer.

The suffix -kor is currently applied only to verbs, and means propensity to, proclivity, inclination.

IX BINAI = Hitz binan (words two by two) makes you think of the litanies of the Catholic rosary and, indeed, we have an example of how these words were paired, in the lead of Èguera serialized in the MLH as F.21.1 and which we’ll see later.

I have not been able to interpret the two final lines of side A:

AI : AXGANDIX:TAGISGAROK:BINIKE / BIN:SALIR:KIDEI:GAIBIGAIT

We have already said that AI was the end of the last word of line 4.

AXGANDIX has a sonority very close to hauxegandik, ablative plural of hauxe, “from these same” (referring only to living beings) but the lack of understanding of the context invalidates this identification.

Now let’s move on to side B, I couldn’t interpret the first line either. It says:

IUNXTIR : SALIRG : BAXIRTIR XABARI (DAI in the 2nd line)

IUNXTIR is an allograph of IUNZDIR = ihinztadur = splash.

SALIRG seems to be an allograph of XALIR, which in other inscriptions such as lead MLH-F.17,1 found in the Iberian town of the Villares de Caudete de las Fuentes, seems to mean “to enjoy”.

BAXIRTIR is very close to basidi = wild ox, bull, auroch.

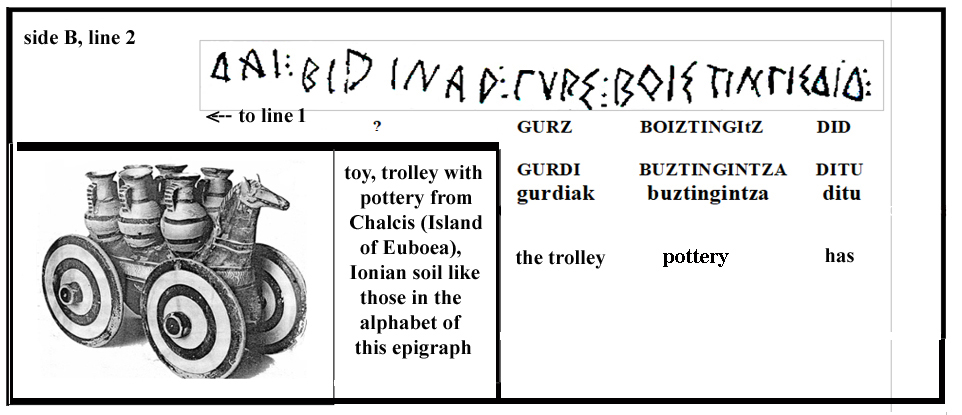

In any case, this is nothing more than suggestions, because the meaning of these lines remains obscure. The beginning of line 2 also does not seem easy to understand, but the second half is. Should we assume that the mentioned pottery is for the IUNZTDIR, that is, the soaking of the concurrence?

From this line, I have only been able to decipher a couple of words, but they seem important to understand some other texts such as the Llíria khalatos one (F.13.5) where, by the way, thee word used to designate the chariot, GURZ o GURTZ also appears.

DITU = has things, formed by the verbal form du = have, and the pluralizing infix -it, here explainable only if we consider buztingintza as a plural or a collective noun, “pottery” instead of ceramics.

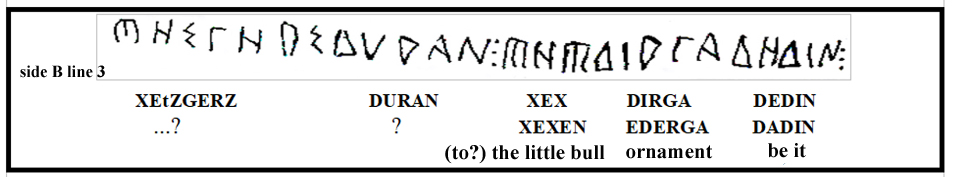

The first 12 signs probably form two words, although no interpunction separates them.

In XEtZGERZ I have not been able to identify any Basque equivalent.

DURAN is very similar to dira = they are, but we will see that in the last line this verb form is written DIRAN. It would not be unthinkable it was a spelling error, above all because numerous indications suggest the Iberians pronounced a U close to the French u or the German ü. The theonym URTZU from the Pontós ostracon has derived into Urtzi in current Basque, as in the toponym Santurzi or the anthroponym Urtzi. Or the opposite case, DOLI (Llíria´s khalatos F.13.5) is currently dolu.

The last three words of this line are so similar to current Basque that they do not require any explanation.

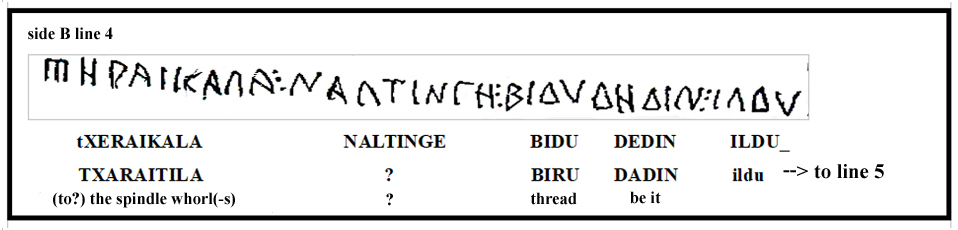

I understand that the differences between TXERAIKALA and txaratila are significant enough for some scholars to disagree with this correspondence. But the similarities are also sufficiently important to consider that, together with the text of the spindle whorl of Valls and that of line 5 that we will see below, we must conclude that the sacrificial bull of the ZALDUDIBAITE, once hanged and dying (URKARA ILUR = urkara hildura = on the gallows mortified or dying, according to the third line of the lead of Enguera MLH-F.21.1) he was castrated with two spindle whorls joined by a thread. This was the “little horn” or “little branch” that the Valls´spindle whorl bailiff had to “reap”.

The carnivalesque hanging donkey of Solsona would be nothing more than a distant reminiscence of the Ancient Carnival, and the Cretan bull-leaping, the Mithraic taurobolium, the Spanish bullfighting, the Sanfermins “encierros” (imprisonment) of the “Sanfermines” of Irunea (Navarra), the “embolats” of Valencia and the Catalan “correbous” (running bulls), would also sink their roots in the Iberian ZALDUDIBAITE and, in all probability, from the Early or Medium Neolithic.

Stonehenge and Carnac which, as we have seen, also have Riversiders origins, cannot respond to any other tradition than that of the Ancient Carnival. Let´s see the last line of the lead.

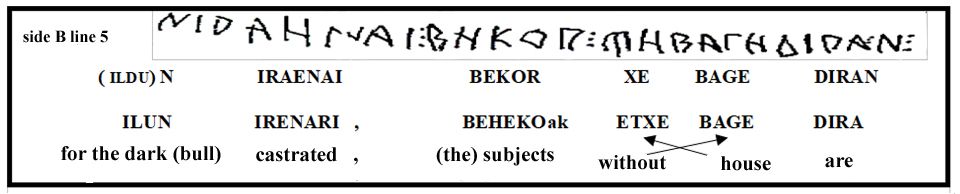

Line 4 said “thread be to the spindle whorl” and now it tells us for whom: for the dark castrated (the ox) in dative suffix –AI = -ari.

BEKOR = beheko(ak) are “the ones below” (behe = below) that is to say the subjects or, perhaps, referring to the earthly human world as opposed to the heavenly divine world?.

“They are without house” suggests that perhaps during the five days of Carnival people could not enter their homes.

Let´s check now whether if the complete text of the both sides of the lead, except the three difficult central lines, has coherence and continuity or, on the contrary, one side is the epistolary response to the other, as some author has intended, based on in the fact that on side A there there are two punctuations, and on B there are three. Any other existing incoherence should appear in this reading.

I put in parentheses the elements that are taken for granted and in italics followed by a question mark in parentheses the elements that generate some doubt. The ellipses represent fragments of the text that could not be interpreted with a high percentage of certainty. Punctuation, as is logical, was not known to the Iberians.

It would, without a doubt, be the reminder of a speech that today we would call “celebration opening speech”, which very possibly the author, designated for such a task, read until he learned it by heart. The style, jumping from detail to detail without an argumentative or logical concatenation, makes you think of much later literature, from the end of the 19th century with literary impressionism.

.

ENGUERA LEAD F.21.1

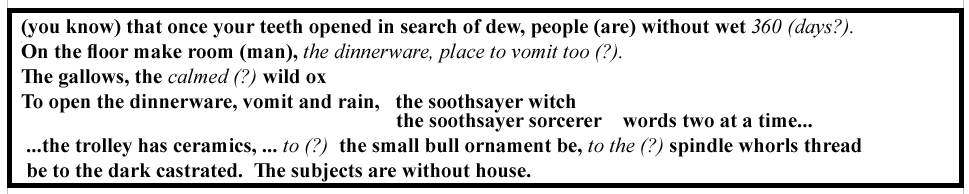

From left to right, Untermann’s excellent transliteration of the 10 lines of the Engera lead.

In the second column, the same Untermann’s version segmented, correcting the devoicing of some plosives and considering the variety of sibilants.

In the third one, the equivalents in Basque and in the fourth one, the meaning in English. I wrote in lower case letters the most dubious interpretations:

Considering the regularity of this lead lines, trisyllabic or tetrasyllabic, Georgeos Díaz-Montexano has claimed to see a poem in it. I don’t think he’s far wrong, as long as we consider the litanies as a poem.

The classic rosary litanies, in Latin, have verses of 5, 6 or 7 syllables that, when pronounced, have a sonority similar to that of the Enguera Lead one. With this opinion in no way do I want to subscribe to the repeated cliché of the pretended religiosity of the Iberians, because I think that some cultural traits that probably have a very different meaning have often been interpreted as religiosity.

.

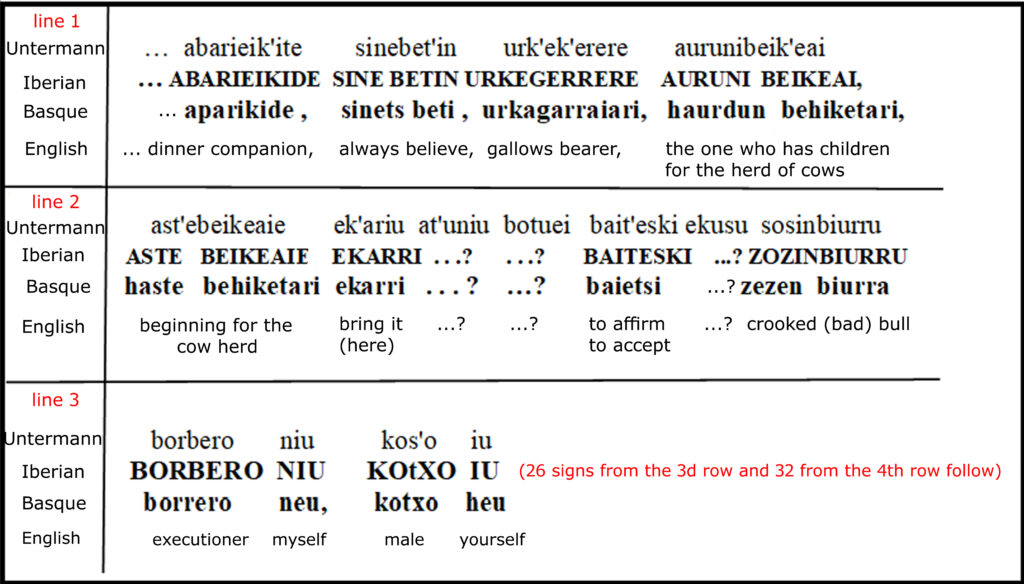

PUJOL DE GASSET LEAD, CASTELLÓ. M.L.H. -F.6.1.

This lead sheet 4.5 cm wide by 44.5 cm long with just over 150 signs and some groups separated by interpunctions, was found in 1851 in the so-called Pujol de Grasset, in the municipal term of Castellón de la Plana.

The first word, of 8 characters, I have not managed to understand, nor half of the 3rd line and all of the 4th.

Apari is not the normal way to say dinner in Basque, but Xavier Kintana’s dictionary includes apari = afari, dinner. It should be borne in mind that the Iberian semisyllabary does not contain f nor v, and that those phonemes are been adquired by Basque language through its evolution (the f) or it has never had (the v).

URKEGERRERE, a word transliterated as urkekerere by most authors, is composed of URKE = urka = gallows and a form of the verb ekarri = bring towards here, fetch. Gallow-bearer would be the equivalent of the Roman insult furcifer which, if it literally meant gallows-bearer, was practically equivalent to the current gallows meat.

AURUNI = haurdun = who has children; it is now applied only to pregnant women, but it´s very well understood when applied to a seed animal, stallion, which “has” or fathers children in the herd of cows.

The forms NIU = neu and IU = heu are emphases of ni = me and hi = you, something equivalent to the French tonic pronouns, moi and toi, as emphases of je and tu.

.

CONCLUSION

It does not seem plausible that great monuments such as Stonehenge or the alignments of Carnac menhirs, the erection of which had required so much labor and so much suffering, were intended to serve as a stage for meetings and assemblies, when to house them, a convenient wooden structure that would require much less effort would suffice.

The Iberian epigraphy shows us and demonstrates that before the Aryan invasions people invested their energies in learning writing, cutting-edge technology at that time, in order to dedicate it to a purely playful purpose, the Carnival party, the festival that compensated for the sufferings of life and that was eagerly awaited throughout the months of the year.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that it was the party that gave meaning to their lives, and as such, it deserved the most strenuous efforts. In the same way that the effort to learn Iberian scripts, which must have seemed so abstruse and arduous to those people, was worth it if the carnival celebration could be improved with it. The construction of large megalithic infrastructures such as those mentioned was equally worthwhile.

.

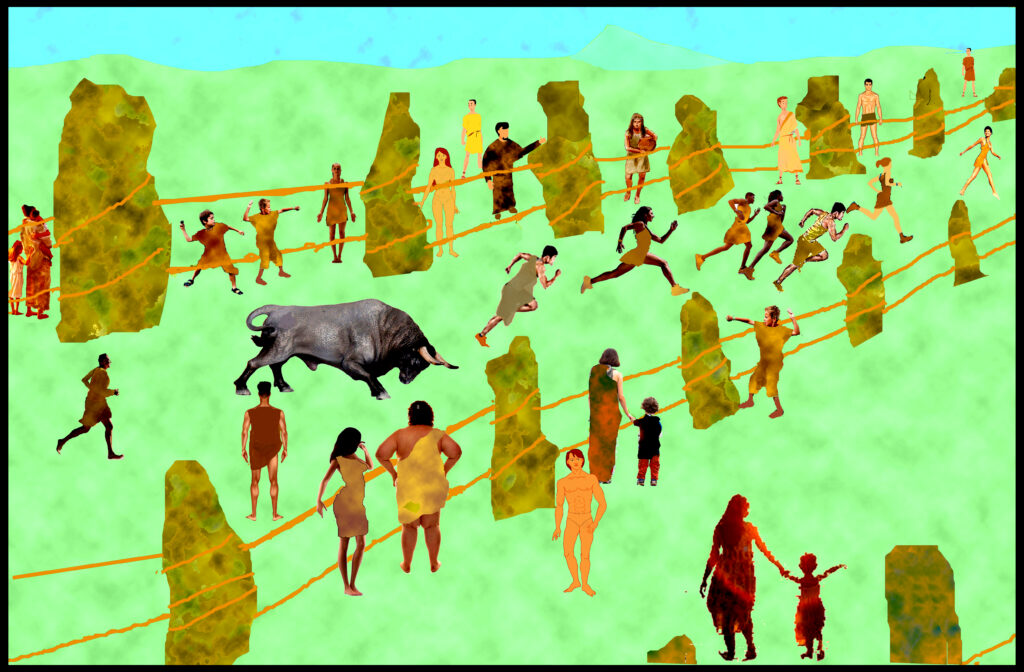

Allowing ourselves to be carried away by a fantasy well based on vestiges and hints of the past, we can imagine an idealized scene of the ancient Carnival:

.

The old bull, considered a theophany of the god Mot, before being hanged on the gallows-cross, used to chase and scare people, just as it is currently done in many places in the Iberian Peninsula, such as the Sanfermines of Iruñea (Pamplona) or the “correbous” of the Catalan Countries.

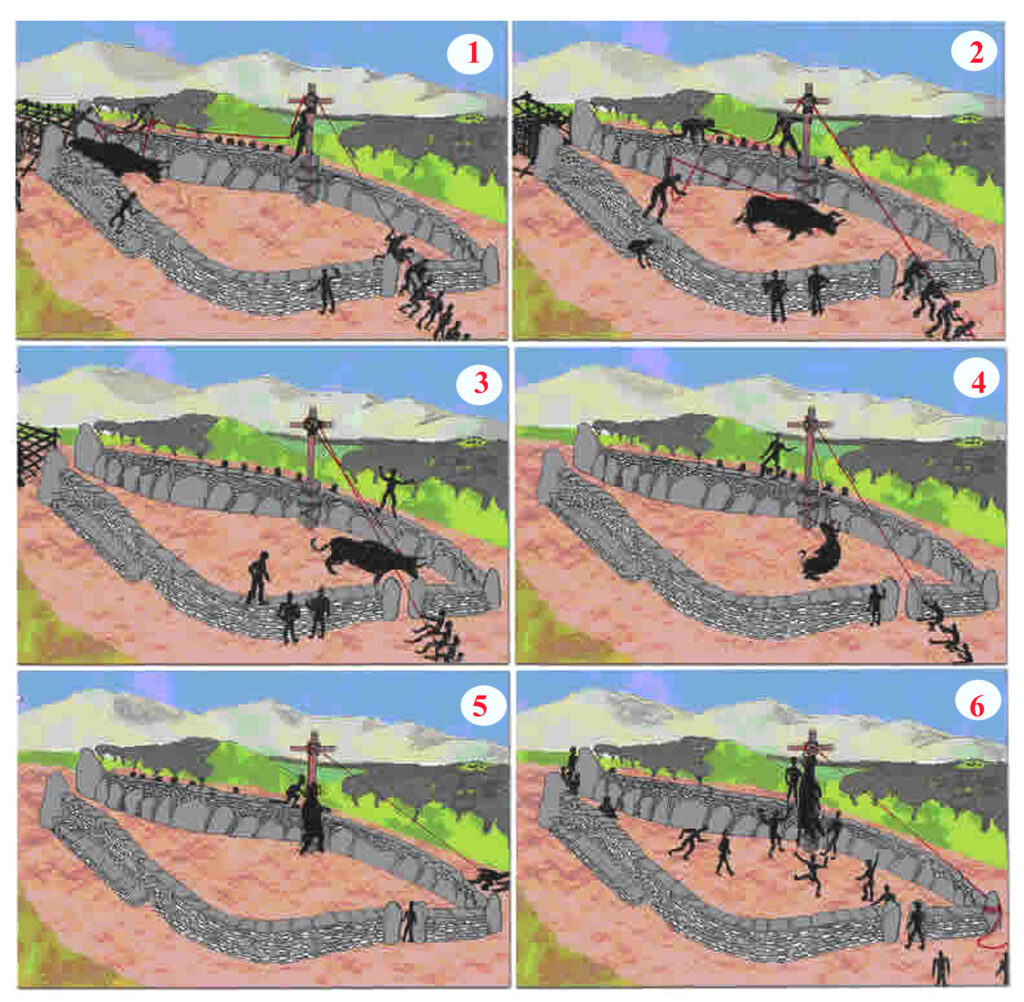

Also, inspired by a modest megalithic monument called Mas Baleta III in my country l’Empordà, an idealization of the death of the sacrificial bull:

Every imaginary representation evocative of an ancient reality, the knowledge of which has proved impossible for us to attain, is a delicate and risky enterprise. But not for this reason should we deny ourselves the right to try to shape scenes based in rationally analyzed and weighed hints.

So let’s try to imagine how the ancient Carnivals could have turned out, from Neolithic times.

1) the cage-cart with the captured auroch approaches the entrance of the enclosure and releases the animal. Taking advantage of the moment of his entrance, a person climbing the wall puts a noose around his neck.

2) the strong men who pull the noose string exit the enclosure through an exit too narrow for the auroch.

3) stopped by the wall, the auroch can’t go any further, the men start to recover the rope.

4) the animal is forced to approach the cross-crane.

5) the auroch begins to be hung from the solid cross-crane strongly tied to a kind of menhir.

6) the beast hangs to death while the attendants receive the supposedly life-giving “rain” (IUNZDIR) by dancing and exulting.

.

FINAL CONSIDERATION:

We are not discovering anything new when we say that historical interpretations of the past are inexorably made from a present that has sedimented in its conscious and not-so-conscious mind, a specific perspective, an interpretative bias.

Often, this bias becomes embedded in the dominant thinking that defines the status quo of a society, a country, or a culture.

This work on Iberian epigraphy was developped in Catalonia (which implies the Spanish state) at the end of the 20th century and the beggining of the 21st. In this context, we cannot underestimate the uniformizing, homogenizing gaze, always ready for, of a Spain in permanent zeal, allergic to any reasoning or assumption that could lay the foundations of an own origin differentiated of some of “their” territories.

Even today, proposing different hypotheses based on the same testimonial bases might seem reckless, in front of the refractory wall, built of performative allegations that have cemented respectable theories, none of them irrevocable or axiomatic, since they aim to reinterpret the past based on vestiges and evidences.

The apprehension and suspicion toward non-Castilian nationalities of the state, especially the Basque and Catalan, carry a force difficult to understand for those who has not experienced them closely.

It is no coincidence that only one of my works on Iberian epigraphy has been accepted for publication in the country’s specialized journals.

One should ask how it is possible that Iberian words so similar to Basque words can create such coherent phrases and speeches, all of them referring to the great festival of antiquity, Carnival.

With three categories of coherence: 1) intratextual: within each inscription

2) intertextual: all the inscriptions, therefore, insistently refer to the same theme;

3) coherence with the historical context of Prehistory and Antiquity and the role played by the bull, not only in Mediterranean societies.

It should not surprise us, therefore, that the opinion of the majority of academics, pressured by the Spanish state apparatus, strives to discredit Basque-Iberianism, reaching such surprising attitudes as that of Professor Javier de Hoz, who maintained the non-existence of an Iberian people, and that the Iberian language was not that of a people but a mere lingua franca used for convenience, by different -and unknown!- ethnic groups.

Even the fact that the aforementioned professor is attached to the “Department of Indo-European Linguistics” at the University of Alcalá may help to understand his interpretative bias.

Certainly, ignorance of our past leads us to the darkness that makes us more vulnerable and distances us from the possibility of directing our efforts to the construction of a world more capable of the common good and equity.

If we cannot achieve this rectification, we fall into the quietism of the desired darkness, to the point of internal emigration.